Why speak differently?

As we study language and evolution, we eventually come across the question: 'Why do people speak differently?' In brief there are four explanations that we can give. People speak differently for...

As we study language and evolution, we eventually come across the question: 'Why do people speak differently?' In brief there are four explanations that we can give. People speak differently for...

- social,

- regional,

- economical

- and historical reasons.

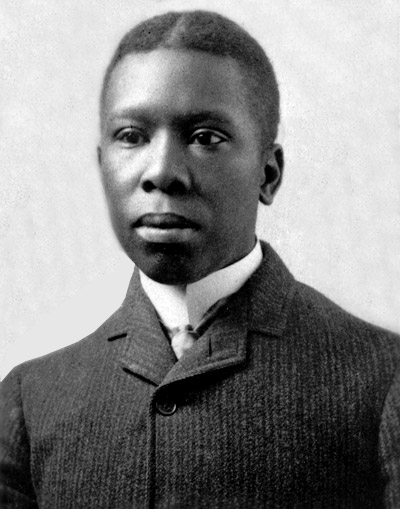

These four reasons are inseparable and difficult to analyze in isolation. Nevertheless, we will look at a poem by Paul Dunbar from 1896 and research the influence of all four factors. By taking this approach, we find evidence from the cultural context to account for deviations from the standardized English that we know and understand today.

Language in cultural context

Before you read the poem by Paul Dunbar below, research a little on the life and times in which he lived. Find out more about his social, regional economical and historical background. Then read the poem, looking for evidence to support why he wrote the way he wrote. You can find a significant amount of information by simply typing 'Paul Dunbar' into any search engine.

| Factors that influenced Paul Dunbar | Evidence of these in the language of his poem |

|

Social - |

For this reason we see much reference to Christianity, the Bible and church. The language of this poem is characteristic of Souther Baptist churches. He refers to "pap's ol' Bible". Another example: "An' on Sunday, too, I noticed, dey was whisp' rin' mighty much." After he dies, the narrator says, "I reckon dat 's whut Gawd had called him for." For this reason we see much reference to Christianity, the Bible and church. The language of this poem is characteristic of Souther Baptist churches. He refers to "pap's ol' Bible". Another example: "An' on Sunday, too, I noticed, dey was whisp' rin' mighty much." After he dies, the narrator says, "I reckon dat 's whut Gawd had called him for."  |

Regional -  Dunbar grew up in Dayton Ohio, though his parents were from the South. He was the only black person at his high school. Dunbar grew up in Dayton Ohio, though his parents were from the South. He was the only black person at his high school. |

Dunbar's use of language in this poem is characteristic of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) found in the South. Even though he spoke standardized English, he wanted his poem to appeal to people from the South. The characteristics of AAVE such dropping th 'r' in 'wah' and the 'th' in 'dey' come from both the influences of Yoruban languages from West Africa and British English which came together on the slave plantations in the South. Dunbar's use of language in this poem is characteristic of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) found in the South. Even though he spoke standardized English, he wanted his poem to appeal to people from the South. The characteristics of AAVE such dropping th 'r' in 'wah' and the 'th' in 'dey' come from both the influences of Yoruban languages from West Africa and British English which came together on the slave plantations in the South.  |

Economical -  Dunbar did not become wealthy or famous from his poetry that was written in Standard American English. Once he wrote in dialect, he received much support. Dunbar did not become wealthy or famous from his poetry that was written in Standard American English. Once he wrote in dialect, he received much support. |

Dunbar received excellent reviews from influential writers after the publication of his poetry in AAVE. The language of the South, which was characteristic of the poor and enslaved, was now being praised by the rich and famous. Dunbar use of AAVE acted as a voice for the oppressed. Dunbar received excellent reviews from influential writers after the publication of his poetry in AAVE. The language of the South, which was characteristic of the poor and enslaved, was now being praised by the rich and famous. Dunbar use of AAVE acted as a voice for the oppressed. |

Historical -  His father, a run away slave, survived the Civil War after fighting for the North. He was entirely of African decent. His father, a run away slave, survived the Civil War after fighting for the North. He was entirely of African decent.  |

He talks about "Lovin' the 'Yankee Blue." The poem is written from a Mother's point of view. Missing her son as he goes to war to fight against slavery. She is proud of him dying for her rights and freedoms. His language is characteristic of African American Vernacular English (AAVE), which is shaped by the history of the Deep South and its African and English roots. He talks about "Lovin' the 'Yankee Blue." The poem is written from a Mother's point of view. Missing her son as he goes to war to fight against slavery. She is proud of him dying for her rights and freedoms. His language is characteristic of African American Vernacular English (AAVE), which is shaped by the history of the Deep South and its African and English roots. |

Further consideration

Why do people use slang? This label seems to have a bad reputation, whereas its definition is closely related to dialect or colloquialism, which are not always looked down upon as harshly. Tom Dalzell offers interesting insight into the notion of 'slang'. Read a sample from his article below and answer the following questions.

-

According to Dalzell, why do people use slang?

-

What arguments do those who are against slang use?

-

Why is slang particularly 'human' according to Dalzell?

-

What types of slang do you use? Do they correspond to Dalzell's description?

The Power of Slang

Tom Dalzell

"Slang pervades American speech to a startling degree. Its popularity can be gauged by the rush of journalists, politicians and purveyors of popular culture to embrace the latest word or phrase to spice up a newspaper headline, stump speech, advertisement or television script.

"Slang pervades American speech to a startling degree. Its popularity can be gauged by the rush of journalists, politicians and purveyors of popular culture to embrace the latest word or phrase to spice up a newspaper headline, stump speech, advertisement or television script.

On the other side of the fence, prescriptive guardians of standard English and morality bemoan slang’s “degrading” effect on public discourse and culture; their outcry further attests to slang’s persistent and powerful presence in everyday American English.

Slang’s popularity and power with speakers of American English should not come as a surprise. By design, slang is wittier and more clever than standard English. As a species that seems to have a genetic inclination to linguistic creativity, we humans (to borrow from Whitman) seem to find endearing slang’s “rich flashes of humor and genius and poetry.” With slang, each generation or subculture/counterculture group has the chance to shape and propagate its own lexicon, and in so doing to exercise originality and imagination. The end result is a lively, playful body of language that is at times used for no other reasons than that it is fun to use and identifies the speaker as clever and witty.

Slang’s primary reason for being, to establish a sense of commonality among its speakers, further ensures its widespread use. When slang is used, there is a subtext to the primary message. That subtext speaks to the speaker’s and listeners’ membership in the same “tribe.” Because “tribe” identity is so important, slang as a powerful and graphic manifestation of that identity’s benefits. At times the primary message is not in the meaning of what is said, but in the very use of slang — a compelling example of how the medium can be the message.” (More on slang and varieties of it can be found here.)

Towards assessment

Further oral activity - Imagine you could interview Paul Dunbar on his use of African American Vernacular English in his poetry in the 1890s. What would he say? Be sure to root your further oral activity in his poem(s), as a primary source of reference.