Exemplar IA: Sample 1a

Teacher notes

Teacher notes

The following page provides you with a sample IA, graded under the new criteria and was part of the sample provided to workshop leaders, during the recent IB workshop training. Sample number 1a - microeconomics is designed to be graded alongside sample number 1b, 1c and (FI). This is an exemplary example of an essay written under the new criteria.

Commentary 1

Title of the article: LED Streetlights Bring Cost Savings, and Headaches, To Colorado Cities

Source of the article: Colorado Public Radio online site

http://www.cpr.org/news/story/ledstreetlightsbringcostsavingsandheadachestocoloradociti es (Accessed 20 February 2017)

Date the article was published: 15 September 2016

Date the commentary was written: 17 March 2017

Word count of the commentary: 792 words

Unit of the syllabus to which the article relates: Microeconomics

Key concept being used: Efficiency

Article

LED Streetlights Bring Cost Savings, And Headaches, To Colorado Cities

The city of Denver is in the midst of a nearly $2 million project to replace lighting poles, fixtures and bulbs on the 13-block 16th Street Mall.

The city of Denver is in the midst of a nearly $2 million project to replace lighting poles, fixtures and bulbs on the 13-block 16th Street Mall.

On their way out: High-pressure sodium lights that have an orange hue. On their way in: White LEDs. “These street lights are about 30 years old. It was time for an upgrade,” said Denver Public Works spokeswoman Heather Burke. “Technology changes. It was time to change with it,”

Denver planned for years before converting the iconic 1970s-era light fixtures along the 16th Street Mall sidewalks to LED lights. They meet new guidelines issued this June by the American Medical Association (AMA).

Across the country, more than 10 percent of outdoor lighting is powered by LEDs. Because the energy savings can be as much as 50 percent, many cities want to make the change. But there are also health implications to consider; LED lights that appear too blue can suppress melatonin production, which can lead to increased diabetes and depression.

The newer LED lights cost the same, provide the same cost savings and last as long as older versions, so “there’s absolutely no reason to put in bad lighting,” said Dr. Mario Motta, who serves on the AMA’s Council on Science and Public Health. “You can put in good lighting.”

Smarter Technology

In June, the AMA issued three core guidelines for cities. It suggested using lights that are 3000 degrees Kelvin or below, referring to the color temperature of lights, where lower numbers appear warmer. Most older versions of LED streetlights installed before 2016 were 4000 Kelvin or above.

The AMA also advised cities to properly shield LEDs to reduce glare, and to make lights dimmable. Professional groups including the Illuminating Engineering Society criticized the guidelines as too specific. The U.S. Department of Energy pointed out that blue light is not unique to LEDs.

Lighting designer Nancy Clanton of the Boulder-based firm Clanton & Associates said the technology that comes with LEDs can offer cities new options.

Clanton has helped design LED streetlights for a number of cities including San Diego and Anchorage. In

San Jose, she worked to install smarter technology that allows the city to dim street lights.

"Right before the bars close, they increase the lighting level so that everyone knows it’s time to go home, and then they decrease it back down again,” she said.

This dimming technology will be installed in Colorado Department of Transportation lights in the coming years. Dimming is also possible on new lights Clanton’s firm helped design for the 16th Street Mall. Denver Public Works spokeswoman Heather Burke said the poles and globe lights will look the same to most. But there’s one noticeable change. Designers have restored a halo of lights that has been dark for years; lost when Denver planners switched light bulb types decades ago.

"The twinkle rings, you can see that ring up there. On the old lights they were inoperable for a long time. So those are restored now. And it’s going to create a brighter more inviting light for folks,” she said.

The AMA guidelines were a challenge for cities that had already invested time and money converting to

LEDs. Some cities like Lake Worth, Florida, changed course and opted for warmer LED streetlights. For Ouray, on the Western Slope, which installed LEDs in 2009, the AMA guidelines released this year were just another bump in a long road adjusting to the new technology.

City Administrator Patrick Rondinelli said Ouray was the first in the state to make the move. A huge selling point was preserving darker night skies.

“In Ouray we’re very fortunate. We can actually still see the Milky Way. You get to Denver, you can’t see that anymore,” he said.

But since 2009, Ouray has noticed a few hiccups as an early adopter of LED technology. LEDs cast a more narrow light pattern compared to other lights. After installation, suddenly large sections of neighborhood blocks went dark. Only the intersections -- where the LED street lights were placed -- appeared lit.

That’s a problem when you have bears walking down side streets.

“As our law enforcement are trying to chase bears around and get them out of the community, they have a hard time seeing a lot of that,” said Rondinelli.

Rondinelli said he doesn’t know what to make of the recent AMA guidelines. Overall, citizen feedback has been positive and cost savings have helped the city’s bottom line.

“We’ve had some lessons learned along the way. But there’s no regrets,” he said.

Since LED technology changes so quickly, there may actually be a benefit in moving slowly.

If a proposed budget item is passed, Fort Collins will swap about one-third of its streetlights to LEDs in 2017 and 2018.

Fort Collins Engineering Manager Kraig Bader said the city hopes to install 3000 and 4000 Kelvin lights with varying brightness depending on how large and busy streets are. It plans to study the results before converting the rest of the city’s lights.

“In essence we’re going slow to go fast later on,” he said.

(Colorado Public Radio, Sep 15, 2016) http://www.cpr.org/news/story/ledstreetlightsbringcostsavingsandheadachestocoloradocities

Commentary

Many problems are associated with the economic evaluation and provision of public goods. How should communities proceed with the installation of LED streetlights in order to ensure that there is allocative efficiency, with the social surplus being maximized where marginal social cost=marginal social benefit (MSC=MSB)?

Streetlights are public goods because they are non-rivalrous and non-excludable. This causes complications when attempting to analyze their advantages (Figure 1).

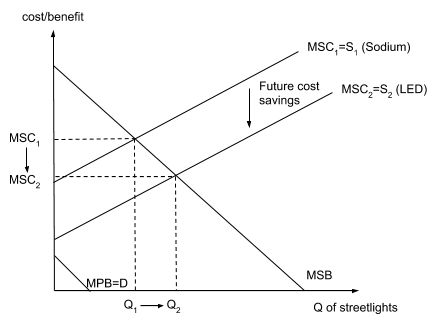

Figure 1: Cost/benefit model for sodium and LED streetlights

The MSC1 curve represents the supply curve of sodium streetlights. The marginal private benefit (MPB), or demand curve for streetlights, does not intersect with the MSC curve because streetlights are public goods. This signifies that the free rider problem is occurring; no-one (or, in reality, very few people) will buy the good because they are all waiting for someone else to buy it. However, the city government ought to pay for these goods, as the MSB of streetlights is high. Before the implementation of LEDs, the optimum or efficient output was Q1 where the MSB curve intersects the MSC1 curve.

The MSC1 curve represents the supply curve of sodium streetlights. The marginal private benefit (MPB), or demand curve for streetlights, does not intersect with the MSC curve because streetlights are public goods. This signifies that the free rider problem is occurring; no-one (or, in reality, very few people) will buy the good because they are all waiting for someone else to buy it. However, the city government ought to pay for these goods, as the MSB of streetlights is high. Before the implementation of LEDs, the optimum or efficient output was Q1 where the MSB curve intersects the MSC1 curve.

Although the article mentions that LEDs “cost the same”, the MSC2 curve for LED streetlights is below the MSC1 curve. This is because private costs are lower, and “energy savings can be as much as 50 percent”, signifying that the costs of using the lights, for many years after implementation, will decrease significantly.

Therefore, the MSC curve will drop. Simultaneously, the efficient quantity of LED streetlights the city ought to acquire will increase from Q1 to Q2. From the diagram, it can be seen that the city can reduce the costs spent on streetlights and at the same time obtain more. The extra lights can be stored until some need to be replaced, implying that costs in the budget for future purchases of the replacement of lights can also be saved.

However, the disadvantages of LED are associated health problems, namely an external cost of consumption (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Negative Consumption Externality of LED streetlights

Because streetlights are public goods, the D (MPB) curve has been shown to be almost irrelevant to the model. Instead, the externality (“health implications” of “increased diabetes and depression”) is shown by the downwards shift of the MSB1 curve to MSB2. The marginal external cost notated in the diagram supposedly measures the per unit negative impact of individual health problems on society.

Because streetlights are public goods, the D (MPB) curve has been shown to be almost irrelevant to the model. Instead, the externality (“health implications” of “increased diabetes and depression”) is shown by the downwards shift of the MSB1 curve to MSB2. The marginal external cost notated in the diagram supposedly measures the per unit negative impact of individual health problems on society.

The diagram shows that the efficient quantity of LEDs is not QP (initially predicted quantity), but QA (actual quantity). It also implies that in order to dissuade cities from implementing harmful LED lights, the efficient “price” of the LED lights at QA will not be cost/benefit2, where MSB2=MSC, but instead at cost/benefit3.

This diagram supports Fort Collins’ argument for changing only part of the city’s streetlights to LED lighting. It illustrates that because of the negative externality, LED lighting, while apparently more “cost-efficient”, has problems. However, the negative externality is probably not so large that LED lighting should be completely eliminated from the city government’s options. It makes sense for Fort Collins to “swap one third of its streetlights to LEDs”. Furthermore, Fort Collins mentioned that they hope to “install 3000 and 4000 Kelvin lights with varying brightness” and “study the results” before making further decisions about whether they will replace the rest of the city’s lights. This exemplifies how communities may use economic models to assess the advantages and disadvantages of public goods, with the aim of improving the well-being of their citizens and reaching allocative efficiency.

However, there are also many limitations to the models above. The models are all static, and do not reflect development of LEDs; an example of rapidly improving, new and clean technology. Research has probably been conducted in order to reduce harmful blue light, and costs of the lights have also been reduced. As the article suggests, the cities have probably taken measures to reduce negative impacts, such as warmer lights, shielding and dimming.

Additionally, more variables should be considered. For instance, the article mentions positive externalities of consumption of LEDs due to the ability to preserve darker night skies. There are also problems associated with LED light patterns being narrow and therefore posing danger of bear attacks. The city must consider different aspects because LEDs are public goods which need to benefit citizens, not only the city budget.

Finally, all the curves and points on the models are qualitative; although they reflect directional shifts, it is impossible to determine the monetary cost of negative and positive externalities. Therefore, applying corrections based on these static models will be unrealistic.

In conclusion, analysis shows that installation of LEDs in some streetlights will save costs while minimizing negative externalities. However, in order to ensure that allocative efficiency is improved, the city government should closely monitor effects on society and citizens’ feedback to make decisions based on reality rather than just on the abstract models.

Assessment criteria

Use the official IB economics IA criteria when assessing this work, available at IA criteria

Criterion A: Diagrams

Level descriptor

The commentary includes two diagrams, both relevantly labeled with an appropriate title. Switches the horizontal axis effectively from “Quantity of streetlights” to “Quantity of LED lights” for the second diagram. The explanations are clear and correct (3/3)

Criterion B: Terminology

Level descriptor

Precise and appropriate economic terminology is used. Concise definition of the relevant term “public good” and a correct understanding of the other terms e.g external cost of consumption is shown by the way they are used (2/2)

Criterion C: Application and analysis

Level descriptor

Cost-benefit analysis is used appropriately and correctly linked to the article. The first diagram contains a demand curve to the left of the optimum, representing the small number of cosumers who might be willing and able to pay the commercial price for street lights. This being the situation in the real world rather than the zero consumers prepared to pay this price in pure public good theory. Situations where the candidate goes beyond the textbook should be rewarded (3/3).

Criterion D: Key concept

Level descriptor

There is recognition that the key concept of efficiency is difficult to calculate and legislate for, given the external costs associated with LED streetlights, Nonetheless it is seen as necessary for governments to try to move closer to achieving efficiency (3/3).

Criterion E: Evaluation

Level descriptor

There is comprehensive evaluationincluded in the commentary and the candidate presents a balance of strengths and weaknesses in the commentary. A short summary conclusion is included (3/3).

Overall comments and grade

Overall this was an excellent commentary which scored full marks - 14/14.

The next commentary in the portfolio can be accessed at: Sample 1b